The Demos ThinkTank recently published an interesting analysis of the Twitter conversations between the Metropolitan Police and the public following the vicious murder of Drummer Lee Rigby in Woolwich.

Twitcidents

The report authors, Jamie Bartlett and Carl Miller, compiled almost 20,000 tweets that included the tag @MetPoliceUK from the week of the Woolwich attack.

They broke down what information people were sharing online, when they shared it and its value as a source of information.

Major incidents of whatever form – disasters, sporting events, terrorist attacks – now inevitably stimulate a massive reaction on Twitter.

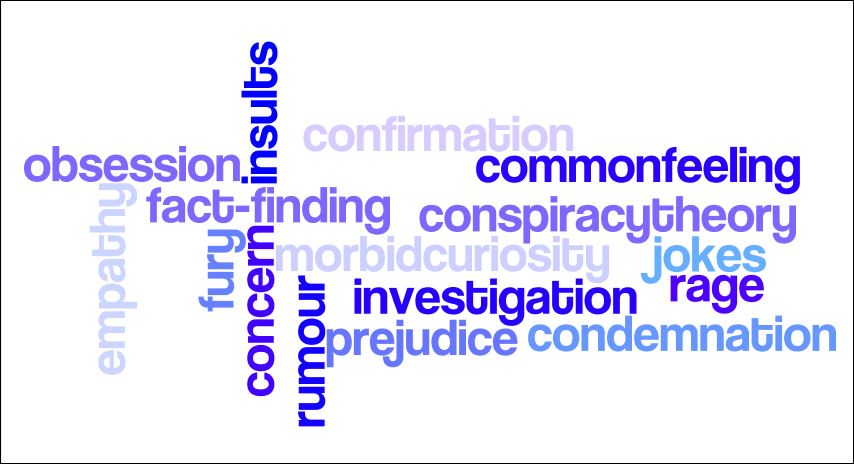

These Twitter reactions tend to be very diverse but typically include the sorts of tweets characterised in the wordle I’ve assembled below:

The question that the Demos report tries to answer is whether there is any value for police services in making sense of this surge of data in real time when confronted with the challenges of a major incident.

The challenges for the Metropolitan Police from the Woolwich incident were many and varied, including:

- Arresting dangerous assailants.

- Investigating a murder which took place on a public street.

- Rapidly assessing terrorist risk and possible further incidents.

- Making themselves available for investigation following the use of firearms in a public area.

- Public Safety and public reassurance.

- Gathering intelligence on the inflammatory and confrontational response from the English Defence League.

- Community relations

As you can see, this list could go on and on – so is there really value in police taking time out to analyse tweets about the incident sent to their @metpoliceuk account?

The Twitter response

One of the first challenges is to remove and ignore the large proportion of tweets which are fake – that is, sent from automated “bot” accounts. In the case of the Woolwich incident, Demos found that 45% of the 19,344 tweets they analysed were produced by a single bot network propagating the following message:

Online crime

However, on the actual day of the murder over a fifth of tweets sent to @metpoliceuk were reports of a possible crime on social media.

The most common type of tweets in this category was the referral of social media content itself as evidence about alleged or supposed on-line and off-line crimes, typically instances of threats, bullying and racism.

Once the nature of the Woolwich murder became clear, tweeters passed on information to the police about possible Islamaphobic plots and threats of violence.

Organised petitions

Another large proportion of tweets (23.2% on the day itself) consisted of systematic attempts by large bodies of people to appeal and petition the police via Twitter to influence their policy. There were two main petitions.

The first was a systematic campaign calling for the arrest of a UK-based Pakistani politician accused of inciting violence in Karachi – which did result in a Met Police investigation.

The other was a campaign to the police to release more information about the Madeleine McCann investigation.

Conversation/engagement

One in nine Tweets to the Met Twitter account on that day were direct requests for police information or action.

Some of these were reporting entirely unrelated crimes and incidents, while others wanted further information around events in Woolwich particularly whether the suspects had been arrested.

(Of course, in the recent Boston bombings, social media was used extensively as the suspects were at large for several days following the terrorist attack.)

Sending off-line evidence

Perhaps most interestingly, one in 40 tweets contained what the Tweeter considered as legally relevant, including eyewitness accounts of a wide range of crimes.

A small proportion of these tweets included potentially very useful intelligence:

Conclusion

The report authors conclude that this surge in social media interaction with police is obviously a mixed blessing; there is a small amount of potentially useful information included within a torrent of hearsay and rumour plus the inevitable general noise of people just participating in the #Twitcident without any particular motive.

It seems to me that there are two key social media challenges to police in the aftermath of major incidents:

- To ensure that there is extra capacity to monitor social media accounts and ensure that accurate, timely and rumour busting information is sent out at regular intervals.

- To have in place a sophisticated system to analyse tweets to provide intelligence and insight.

- Although short, the Demos report is well worth reading in full.

What’s your experience of the pros and cons of social media following a major incident?